On December 11, the Review Board of the U.S. Copyright Office affirmed the refusal to register yet another AI-generated work. The decision follows the Office’s refusal to register Dr. Stephen Thaler’s A Recent Entrance to Paradise (which was affirmed in federal court, reported here, and is on appeal to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia), Kris Kashtanova’s Zarya of the Dawn (reported here), and Jason Michael Allen’s Théâtre D’opéra Spatial.

Two of those three works—Kashtanova’s Zarya of the Dawn and Allen’s Théâtre D’opéra Spatial—were created using Midjourney, a platform the Office found to generate images in an “unpredictable way,” and to interpret prompts as mere “suggestions” such that “Midjourney users lack sufficient control over generated images to be treated as the ‘master mind’ behind them.” And Thaler never made this “human control” argument before the Office; instead, he claimed that his AI model—DABUS—was the sole author of A Recent Entrance to Paradise, and his application was refused for failing to satisfy the “Human Authorship Requirement.”

The Decision

Ankit Sahni, however, did not generate SURYAST using Midjourney, nor did he waive arguments regarding control of RAGHAV, the generative AI tool he used to generate that work. Like Midjourney, RAGHAV was developed through machine learning and “trained” on a large image dataset. Yet instead of generating images from text prompts, RAGHAV transfers the style of one image to another based on a user-determined numerical value for the degree of the transfer.

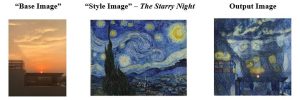

Here, Sahni used his own photograph as the “base image,” Van Gogh’s The Starry Night as the “style image,” set a numerical value, and obtained SURYAST, the output image shown below:

In affirming the refusal to register SURYAST, the Review Board concluded that the work is not registrable because Sahni “exerted insufficient creative control over RAGHAV’s creation of the Work.” Specifically, the Board found that SURYAST “is not the product of human authorship” because “the expressive elements of pictorial authorship were not provided by [him].” The Board further observed that Sahni’s three “inputs” into RAGHAV—his base image, the Van Gogh style image, and a numerical value—did not determine important creative aspects of the work (listed below), finding instead that RAGHAV made those choices. For example:

- How to interpolate the base and style images in accordance with the style transfer value;

- where the elements of the work would be placed;

- whether the elements of the work would appear at all; and

- what colors would be applied to the elements of the work.

Importantly, unlike Thaler, Sahni did not waive arguments that he controlled the AI system at issue; he made them, but the Board simply was not persuaded. It noted that Sahni’s comparison of RAGHAV to photo-editing software like Adobe Photoshop “conflicts with other information in the record” because he admitted that RAGHAV generates content based on “features learned from user-provided images.” These inconsistencies led the Board to conclude that the creative expression in SURYAST “is a function of how the model works and the images on which it was trained—not specific contributions or instructions received from Mr. Sahni.” The Board also rejected the argument that Sahni’s choice to apply a “Starry Night style” to his photograph was protectable, characterizing that choice as an unprotectable idea, not protectable expression.

This Copyright Office decision is likely to frustrate visual artists that continue to believe that generative AI outputs should be protected by copyright. The Office’s reasoning also fails to answer the questions raised by its prior decisions refusing registration of Zarya of the Dawn and Théâtre D’opéra Spatial, namely, whether the Office’s examination of registration applications is more relaxed for traditional media than for AI-generated content.

Takeaways

While the Office’s decision on SURYAST is consistent with its previous decisions on the registrability of AI-generated content, a few things stand out.

First, when Sahni applied to register SURYAST, he listed himself as the author of “photograph, 2-D artwork” and “RAGHAV Artificial Intelligence Painting App” as the author of “2-D artwork.” The Office’s refusal to register SURYAST is the first decision on an application to register an AI-generated work based on joint authorship with a generative AI system, and confirms that this strategy is no more effective than user-as-author (Kashtanova, Allen) or AI-as-author (Thaler).

Second, the decision raises new questions about the Office’s approach to AI-generated works. In refusing registration, the Office rejected Sahni’s argument that his contributions to SURYAST were sufficient to make him the author because he not only chose the inputs to RAGHAV but also created them, i.e., the base image. In doing so, the Office found that SURYAST was a derivative work, focusing solely on the “new authorship,” and excluded that base image from consideration. This raises the question: if an author takes a photograph as an interim step in a creative process (i.e., to use as a generative AI input, but not to create a standalone, photographic work), is it fair for the Office to filter out that photograph in considering the author’s contributions to the final work? Does that analysis unfairly focus the lens of traditional media on new, AI media?

Third, the decision raises interesting questions about the copyrightability of style. It doesn’t take a copyright expert to know that Sahni could never own Van Gogh’s style (even on the starriest of nights). But had the Board viewed Van Gogh’s style as protectable to begin with, it might have observed that Van Gogh’s style was not Sahni’s to claim (or was in the public domain). Instead, the Board found that applying Van Gogh’s style was an unprotectable idea. In its August 30, 2023 Notice of Inquiry on Artificial Intelligence and Copyright, the Office described “style” as an unprotectable “personal attribute,” so questions remain whether an artist’s style can constitute protectable expression. What if, for example, Sahni had used RAGHAV to sample his own style? Would that be enough to register the output? We may soon find out.

The decision of the Review Board of the U.S. Copyright Office affirming the Office’s refusal to register SURYAST can be found here.

RELATED ARTICLES

Ability of AI to Invent Struck a Resounding and Uncompromising Blow

Internet & Social Media Law Blog

Internet & Social Media Law Blog