Since my last post on the subject (“LinkedIn Grapples with the Ripples of a 2012 Data Breach”), there have been several developments related to LinkedIn’s 2012 data breach. First, in May, LinkedIn announced it has finished the process of invalidating passwords at risk, specifically LinkedIn accounts that had not reset their passwords since the 2012 breach:

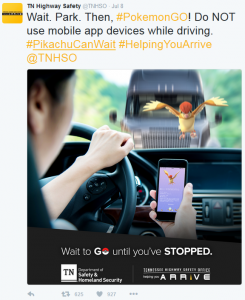

News of Note for the Internet-Minded – Pokémon Go Edition

Even as the initial furor surrounding the release of developer Niantic’s Pokémon-themed ap has subsided, the issues raised by the mass embrace of the augmented reality-flavored game continue to merit attention from lawmakers, games makers and players alike. Here are a few of the recent stories involving Pikachu, Charizard and company.

Are There Phishing Holes in Your Cybersecurity Insurance?

A robust cybersecurity strategy involves sophisticated, overlapping protections. Along with up-to-date technology, well-trained employees and vigilant IT professionals, comprehensive insurance coverage is an often necessary ingredient of any protective “moat” shielding a company from damaging cyberattacks. Yet does a company’s cyber insurance package actually protect it from one of the most common forms of cyberattack—when a hacker goes phishing? In her post “Phishing for Insurance Coverage” on Pillsbury’s Policyholder Plus insurance blog, our colleague Peri Mahaley examines a variety of surprising phishing-related exclusions one might discover in a company’s cyber coverage.

Pokémon Go and the Evolving Arena of Clickwrap Enforcement against Children

According to the official Pokémon website, “kids all over the world have been discovering the enchanting world of Pokémon [for over 15 years].” Not surprisingly, many of us who used to be kids in the 15+ years are playing Pokémon Go, but who would have expected nearly 4 of every 5 Pokémon Go players (almost 80%) to be adults. Put into perspective—at Pokémon Go’s peak of 25 million daily active users, close to 20 million adults may have been playing the location-based augmented reality mobile game every day! Still, that also means at least one out of every five players are children, which in turn represents millions of daily active users against whom one or more provisions of Pokémon Go’s Terms of Service (TOS) might be unenforceable.

Algorithms and the Perception of Bias

On Saturday, July 23, Facebook acknowledged its anti-spam systems had briefly and accidentally blocked links to WikiLeaks files containing internal Democratic National Committee (DNC) emails. WikiLeaks had released 19,000 leaked documents from the DNC containing communication between Democratic Party officials on Friday, July 22. The following day, people tweeted screenshots of an error message they received when attempting to post links to the leaked documents: “The content you’re trying to share includes a link that our security systems detected to be unsafe.”

On Saturday, July 23, Facebook acknowledged its anti-spam systems had briefly and accidentally blocked links to WikiLeaks files containing internal Democratic National Committee (DNC) emails. WikiLeaks had released 19,000 leaked documents from the DNC containing communication between Democratic Party officials on Friday, July 22. The following day, people tweeted screenshots of an error message they received when attempting to post links to the leaked documents: “The content you’re trying to share includes a link that our security systems detected to be unsafe.”

How Does One Insure an Autonomous Vehicle?

Transformative technologies do not just change their own industries—they cause a ripple effect throughout adjacent, more mature sectors. Just as the sudden, mass embrace of augmented reality in Pokémon Go opens up a number of liability concerns, so, too, will the advent of autonomous vehicles (the embrace of which is markedly more measured, but just as inevitable) necessitate changes in the insurance industry and the products it provides. In their post, “Robot Take the Wheel: Insurance Implications of Autonomous Vehicles,” colleagues Peter Gillon and Bryan Coffey examine some of the likely paths these changes may take.

Pokémon Go Ushers in a New, Augmented World of Legal Liability Concerns

We predicted last year that 2016 would be the year of Pokémon. This prophecy came true last week within just two days of the Pokémon Go launch. The location-based augmented reality mobile game/app quickly surpassed Tinder in daily users and neared Twitter’s totals (and as of yesterday, surpassed them), with its users spending twice as much time engaged with Pokémon Go relative to apps like Snapchat. This explosion has helped shares of Nintendo, partial owner of both the Pokémon Company and Niantic (which developed the game), grow over 50% in three trading days since the app’s launch. In the aftermath of the Pokémon takeover, it’s a good time to revisit some of the potential legal implications.

We predicted last year that 2016 would be the year of Pokémon. This prophecy came true last week within just two days of the Pokémon Go launch. The location-based augmented reality mobile game/app quickly surpassed Tinder in daily users and neared Twitter’s totals (and as of yesterday, surpassed them), with its users spending twice as much time engaged with Pokémon Go relative to apps like Snapchat. This explosion has helped shares of Nintendo, partial owner of both the Pokémon Company and Niantic (which developed the game), grow over 50% in three trading days since the app’s launch. In the aftermath of the Pokémon takeover, it’s a good time to revisit some of the potential legal implications.

Warner Bros.’s “Paid to Play” Disclosures Draw FTC Action

Earlier this year, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) went after Warner Bros. Home Entertainment Inc. for not clearly representing that several digital influencers were paid as part of a marketing campaign for the video game Middle Earth: Shadow of Mordor. (See our prior posts on FTC enforcement of its disclosure requirements.) According to the complaint, these influencers were paid amounts ranging from hundreds of dollars to tens of thousands of dollars and received advance-release copies of the game with instructions on how to promote the game. The sponsored videos were viewed more than 5.5 million times. One very popular influencer, Felix Kjellberg, known as “PewDiePie” on YouTube, created a video that has been viewed over 3.7 million times by itself.

News of Note for the Internet-Minded – 7/7/16

Snapchat announces a seismic shift, Microsoft looks to DNA for your long-term storage needs, and authorities try to get out ahead of some of the predictable consequences of Pokémon Go’s arrival. (Please look where you’re walking as you try to catch them all.)

A Little “Mayhem” Reveals Limits to Immunity Provision of Communications Decency Act

As a general rule, a website is not held liable for the content its users post on its platform. The Communications Decency Act (CDA) immunizes websites from lawsuits by not treating the website as the publisher or speaker of content posted by its users. It also allows websites to edit and remove content that could be obscene, lewd and objectionable without the website incurring liability for failure to remove other similar content. Courts have even gone as far as not holding websites liable for defamatory, offensive or infringing posts by its users even when such websites invite visitors to post potentially defamatory statements, so long as the website did not materially contribute to the actual offensive content of the post. While courts have applied this protection broadly, a recent Ninth Circuit decision declined to do so.